Documentation by Karen Asher

Documentation by Karen Asher

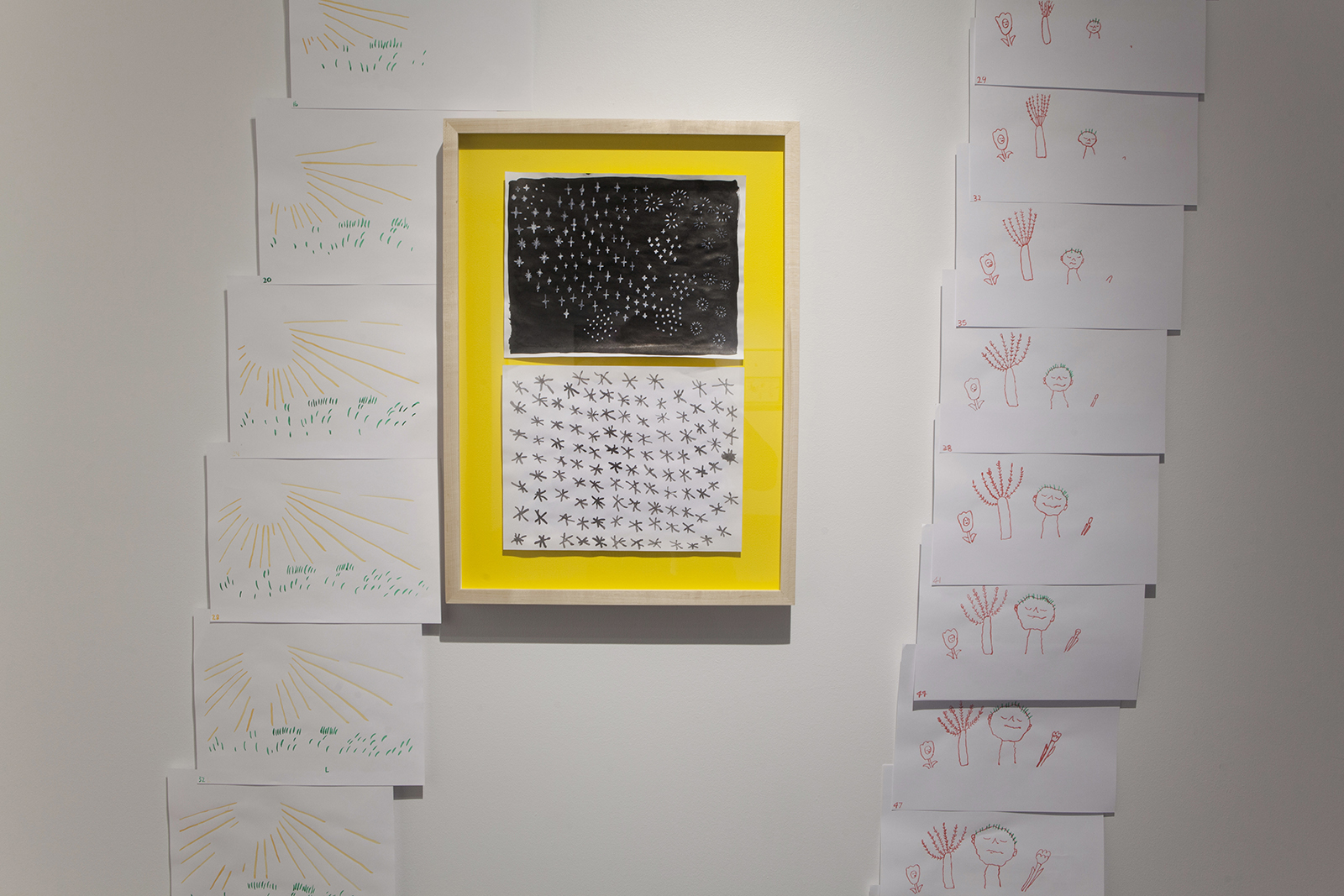

Draw we are together

Natalie Baird & Toby Gillies

Galerie Buhler Gallery

May 8, 2024 - July 21, 2024

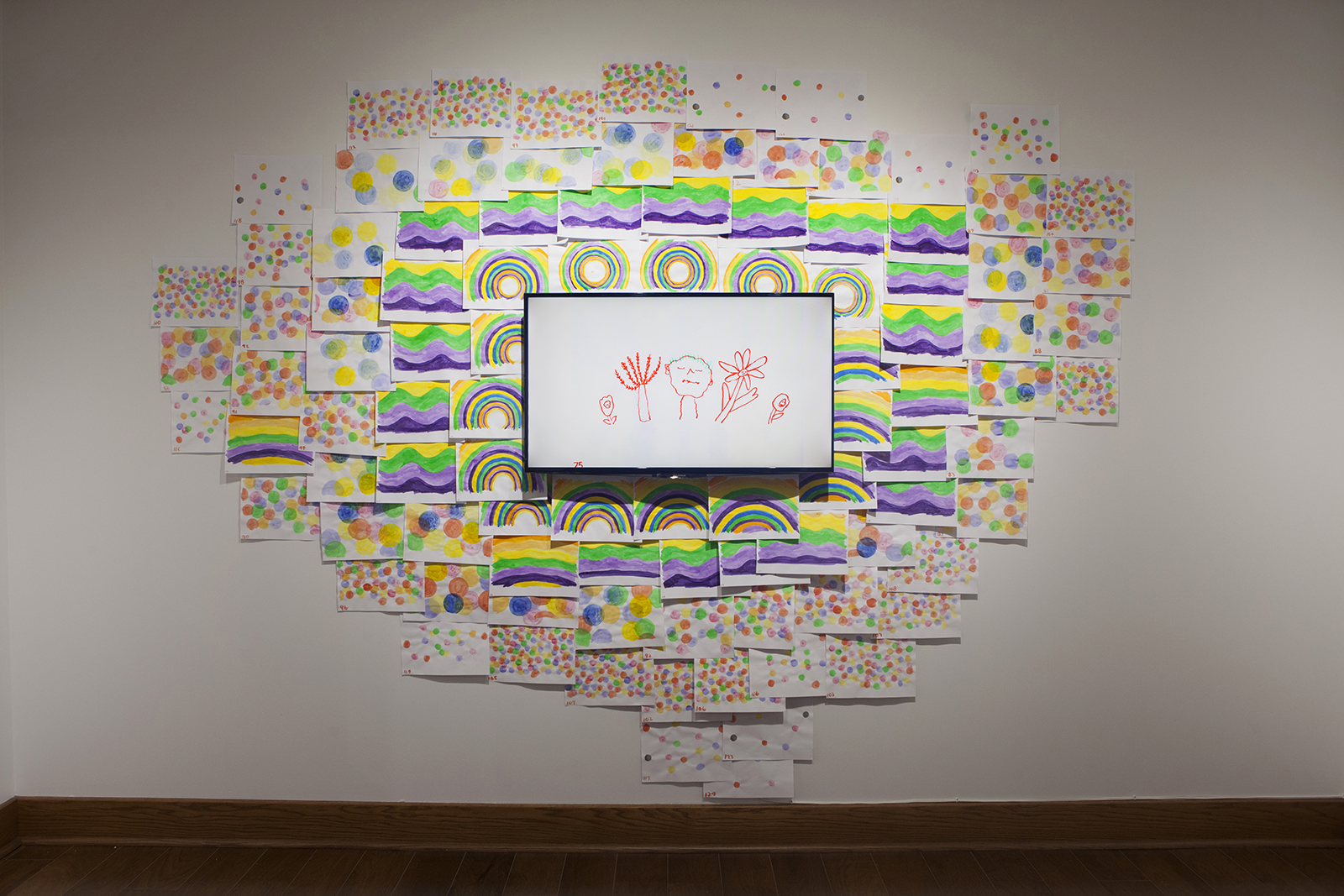

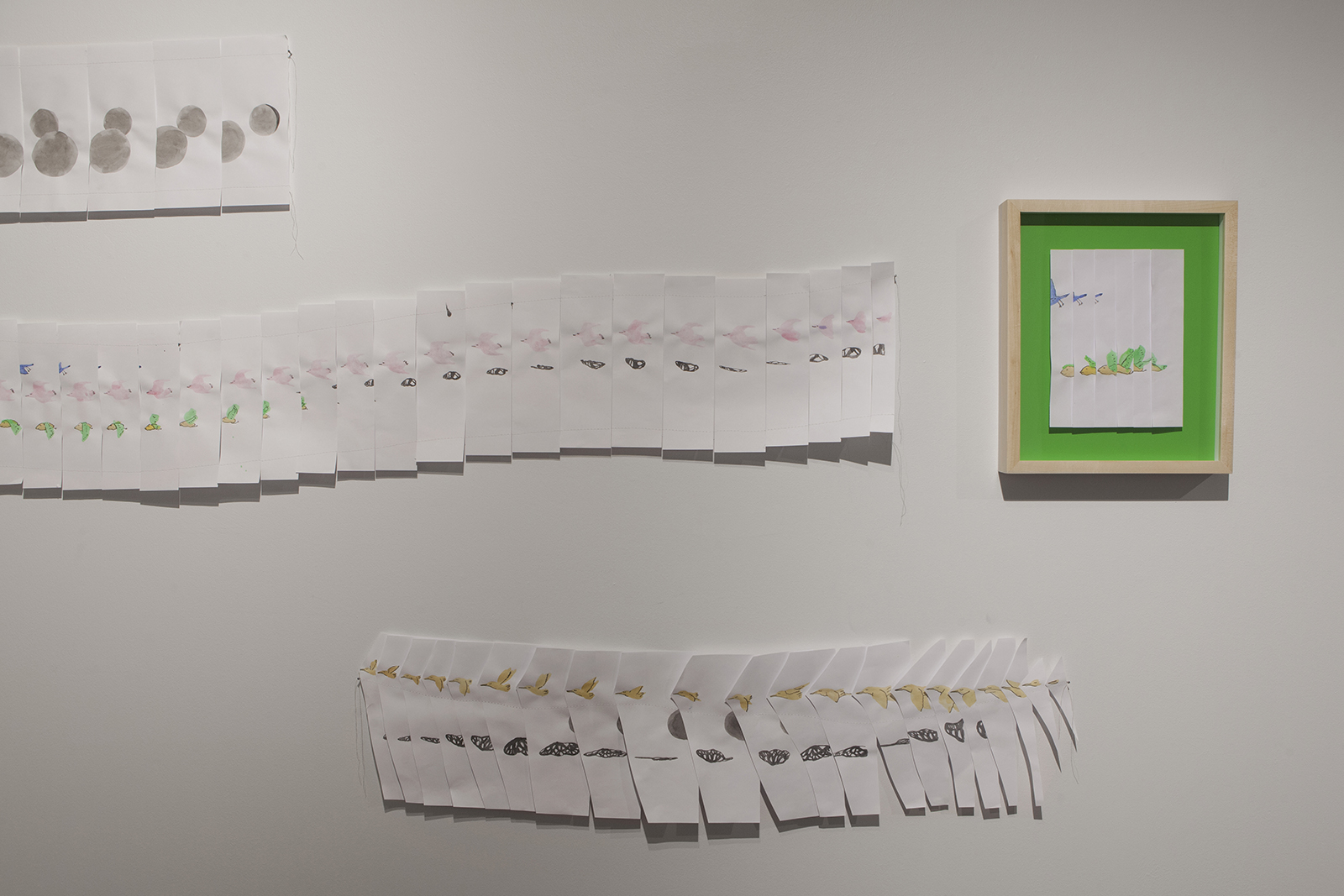

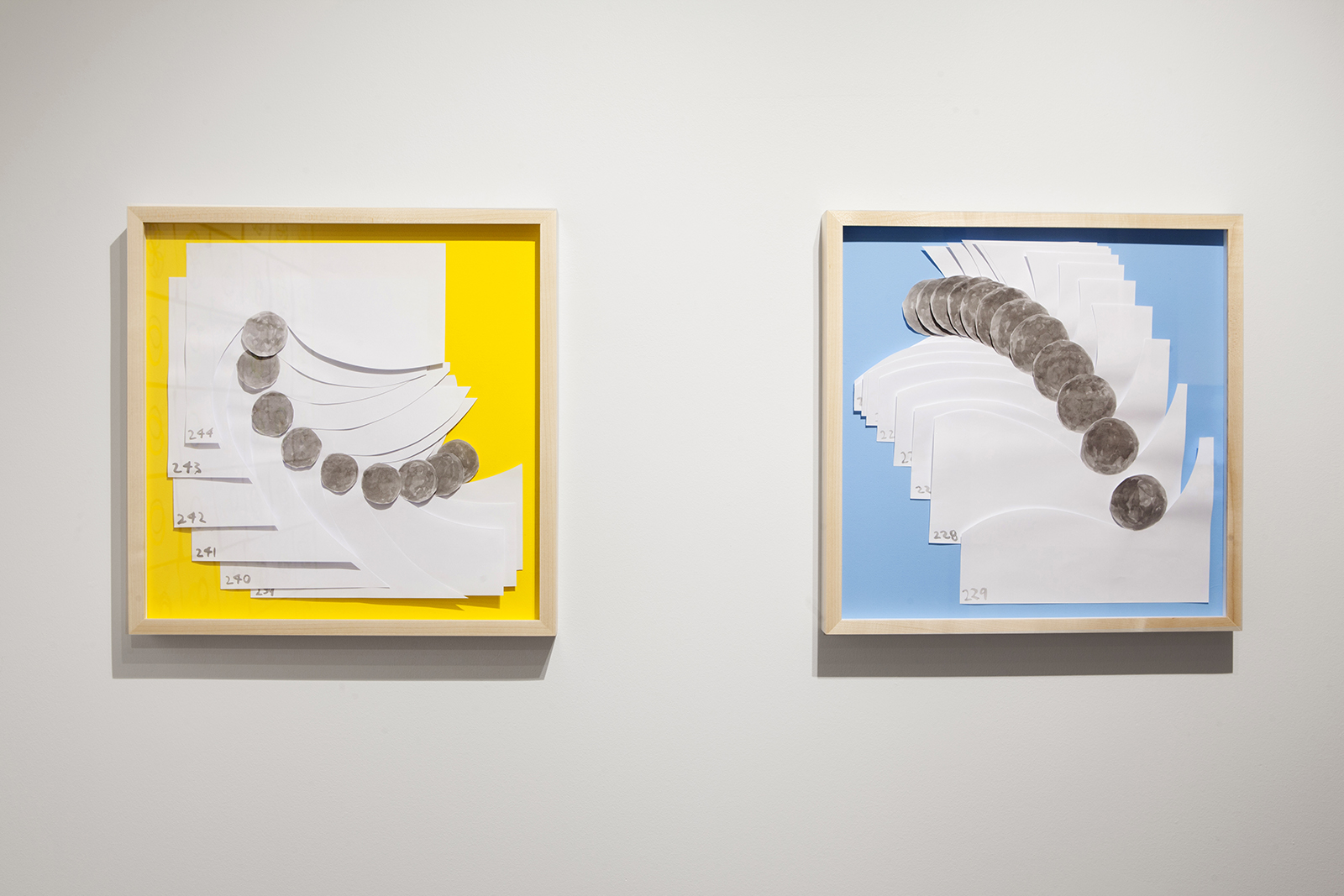

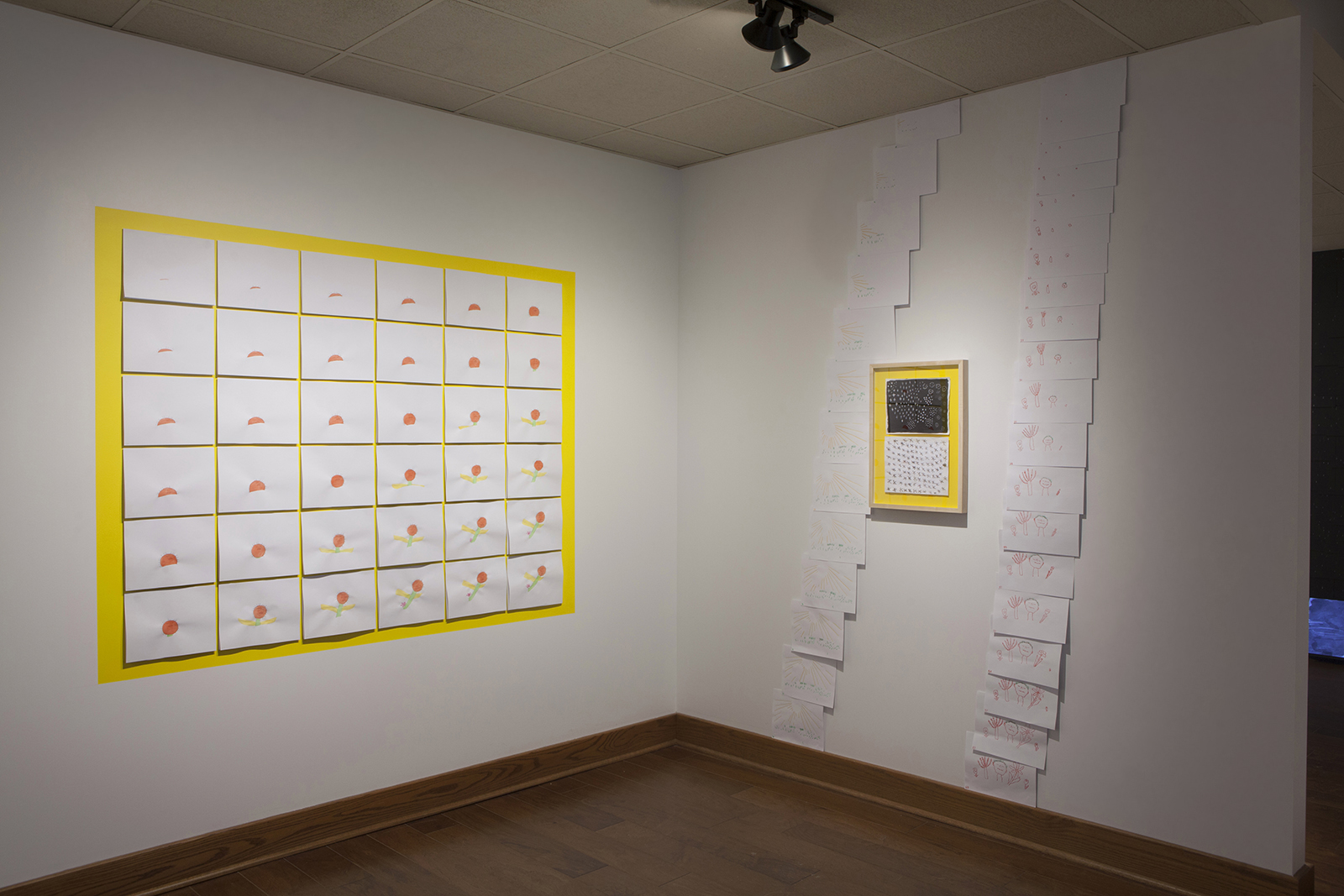

Draw we are together is an exhibition based on the short film “Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying,” created by Natalie Baird and Toby Gillies and produced by the National Film Board of Canada. In this hand-drawn animated documentary, mother, elder, and narrator Edith Almadi navigates the grief of losing her son by following his request to “draw we are together.” The exhibition transforms animation ephemera into new artworks that connect themes of grief, memory, and imagination within the same cosmos, and shares the magic of frame-by-frame animation as well as the labour it requires. The film and exhibition are the result of ten years of creative collaboration with each other and in their community, following ideas and processes that grow from enjoying time making art together each week.

With the generous support of the St. Boniface Hospital Foundation, the Manitoba Arts Council, and the Winnipeg Arts Council.

Exhibition essay by hannah_g

Disponible en français

In the last shot of Natalie Baird and Toby Gillies’ film, Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying, we see Edith Almadi, the film’s protagonist, through a window. She is slightly obscured by reflections on the glass and the geranium on the sill but we can still see her expression. Her eyes are raised and her lips slightly parted. It’s as if she is listening to something, but we know, rather, that she is seeing something with her mind’s eye: she is imagining being with her son and it is making her happy. After a couple of seconds, her gaze lowers, her mouth closes, and with a small shake of her head, we witness her return to the world.

Edith is an elderly woman who emigrated from Hungary to Canada many years ago and her speech is still inflected with her mother tongue. She feels very much alive, she tells us; she is old but she does not feel any different, only now, she notes, there is “just something missing.” Her son, a middleaged man, died recently. Through lovely animations, Natalie and Toby show how Edith’s imagination enables her to remain close to him. She thinks of him floating through the air with a butterfly flying above him, or she pictures him as the sun and herself as the moon twirling in circles together where they “chase the clouds away, forever.” She sees them both surrounded by people she loves, all of them happy. Throughout the film we move between lively animated scenes full of bright colours, patterns, butterflies, fantastical f lying beings, the sun and moon, and shots of Edith in her modest room in a personal care home where the weather always seems overcast. Yet the dim light from the window still illuminates Edith, while throwing the rigid, straight lines of institutional furnishings into sharp relief. There are moments, however, when those hard lines give way to the geranium’s blurry green and pinky reds or drawings creep in and take over; both suggest the ever-present possibility of transcendence offered by Edith’s imagination.

Toby and Natalie met and became friends with Edith through a long-running art program they led in a care home in their neighbourhood in Winnipeg. While drawing and making art together, they began recording Edith speaking and telling stories. “Our initial motivation for interviewing Edith was to save memories for ourselves – we find the way she speaks fascinating and poetic,” Natalie and Toby explain in their statement about this project. Edith’s drawings are similarly powerful. “When Edith looks at her drawings, she sees her memories and fantasies. She is able to escape her physical circumstances through entering her marker and watercolour worlds,” they note. The animations in Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying, they go on to explain, “are an expression of our shared imagination, incorporating imagery from our minds, Edith’s words, and the drawings we made together.”

Our imaginations are, in part, grown by listening to stories and creating images of their places, characters, and objects in our minds. This happens for many people during childhood with relatives and caregivers reading aloud from books or through listening to audio stories. Being read to is an intimate experience and can create a special bond between the reader and listener. Although children are regarded as the experts in the realm of stories and imagining, it is hugely important to each of us, and can bring great relief in stressful situations. I remember reading to my mum when she was dangerously ill on an acute care ward; it was one of the only things that could distract and calm her and so enable her to rest, which fortified me as well. They were from a book she had given me when I was a child and we had both loved the stories. At her hospital bed our roles shifted and a circle formed when I began reading to her. Something similar is happening with Edith’s imaginings in the film. She reassures her son and herself by telling him each night she will see him soon. “You open your arms as a farewell. / This is how you whisper goodnight / While you are walking / in the land of fairies... / My little boy, goodnight.”

This exhibition, Draw we are together, is timed to coincide with the National Film Board of Canada’s official launch of Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying. It takes an unbelievably long time to make an animation: hundreds and hundreds of drawings and paintings were produced to complete a seven minute film. During our conversations and visits over the last year, I became very interested in Toby and Natalie’s drawings, which feature identical or near-identical images repeated on scores of numbered sheets of paper. The artists have a simple style but seeing so many of their drawings at the same time makes evident their tremendous skill as illustrators and animators, able to deftly repeat and alter images in specific and often subtle ways to achieve an effect, a transition, or the illusion of movement.

This film, like all films, is comprised of a series of moving multiples and within its companion exhibition, you can see some of the individual frames comprising scenes all at once, rather than in the too-quick-to-see linear composition of film. I’m reminded of the chronophotography (a series of photographs of a moving object taken to show the successive phases of its motion) of the nineteenth century photographer Eadweard Muybridge, who used multiple cameras trained on people and animals running or gesturing in order to capture the different aspects of their movement. The individual frames we see in Natalie and Toby’s exhibition as sets of drawings show one movement leading to another but they also portray an intense, sustained creative process. The stacks of paper they accumulated over the months in their studio are monuments to the attention and care they gave to Edith’s story as well as to their daily commitment to the project, to Edith, and to each other. Whereas Toby and Natalie present elements of Edith’s inner world in the f ilm, the exhibition presents the shared creative world that underpinned it. As collaborators and directors, the artists worked day after day for two years on this project listening to music, talking, drawing, constructing, and experimenting to create Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying and it also shaped the ongoing life of their relationship as art partners and friends. Their creativity was combined through Edith’s story to produce not only a film but a huge body of discrete pieces that can be engaged with as artworks in their own right. The exhibition and film both exult in their flourishing, overlapping imaginings, the joyfulness, poignancy, and comfort that can arise when time’s linearity and the restrictions of circumstance recede:

“I go everywhere I want to … / I can live a hundred lives all over again. / Still the beauty. / It’s imagination. / Just like a child. / Totally free.”

With thanks to Blair Fornwald for their invaluable edits of this essay.

Animation epherma from Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Crying